When Princeton history professor Sean Wilentz was a student at Columbia in 1969, a new Bob Dylan record titled The Great White Wonder began popping up in record stores. Completely unsanctioned by Bob Dylan or his label, it mixed Basement Tapes material with informal recordings of Dylan during his early folk period between 1961 and 1962. “It was revelatory,” Wilentz says. “You got to hear Dylan talk, make jokes, boast. It brought you the person behind the idol.”

The Great White Wonder became such a sensation that it essentially gave birth to the entire bootleg industry. And even though acts like Led Zeppelin, the Grateful Dead, Pink Floyd, the Rolling Stones, and the Who were very popular in this world of illegal releases, the number of Dylan bootlegs on the market dwarfed them all.

“The bootleg records, those are outrageous,” Dylan complained to Cameron Crowe in 1985. “I mean, they have stuff you do in a phone booth. Like, nobody’s around. If you’re just sitting and strumming in a motel, you don’t think anyone’s there. It’s like the phone is tapped…Then you wonder why most artists feel so paranoid.”

In 1991, Dylan decided to beat the bootlegers at their own game by launching the Bootleg Series. It’s stretched to 16 volumes over the past three decades, chronicling practically every era of his career, and they were all overseen by Dylan’s longtime manager, Jeff Rosen. But for the forthcoming 17th volume, Through the Open Window, 1956-1963, which concentrates on Dylan’s earliest recordings during his folk period, the baton was passed to Wilentz.

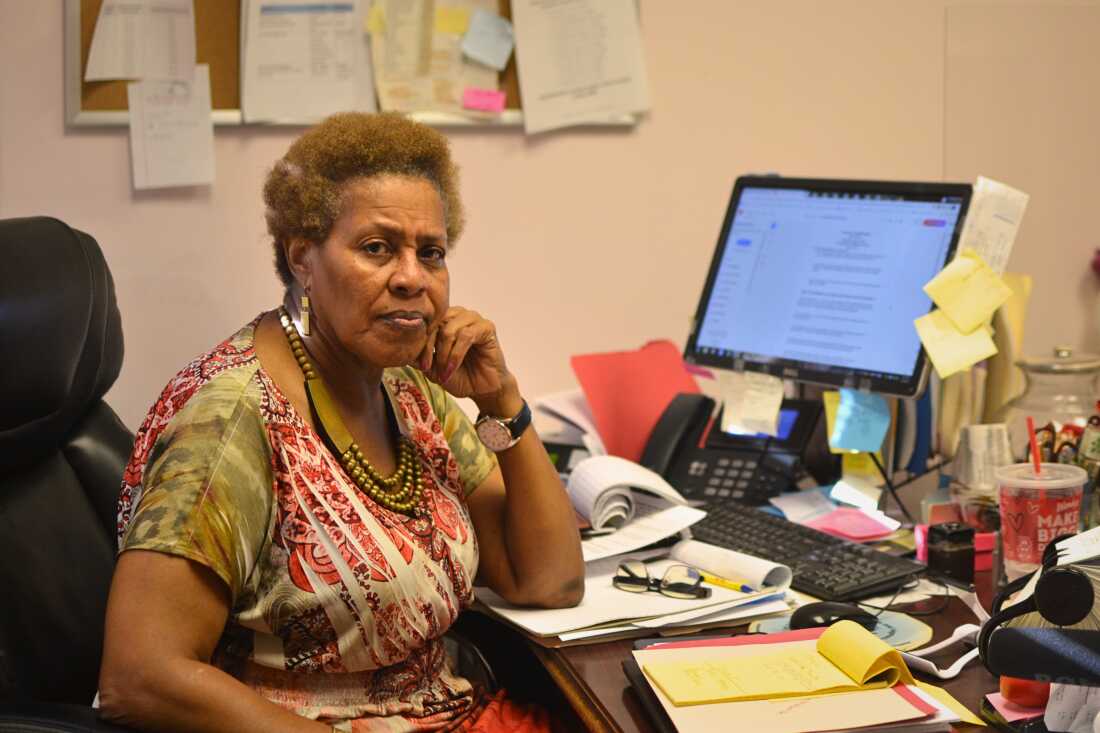

Not only is Wilentz a renowned Dylan scholar and author of the stellar 2010 book Bob Dylan in America, but he was around the Greenwich Village folk scene as a kid and knows its history like few others. In addition to combing through all the tapes from this time period — many unheard by even the most serious Dylan fans — he also contributed a 125-page essay to the box. We hopped on a Zoom with Wilentz to hear about his long history as a Dylan fan, the creation of the box set, and what he hopes to see come out in the future.

I’ve been hearing rumors of some sort of “Villager” box set for years. It’s exciting that it’s finally here.

Yeah, I know it is. I heard about it first at a party for the [2023] book, Mixing Up the Medicine. There was this rumor floating around, and I said, “Oh, that sounds interesting.” But in some ways, people have been wanting this for forever because ever since the first Bootleg Series in 1991 or even Biograph [in 1985], there’s always been this fascination with Dylan’s very, very early career. Finally, we got together to do this.

My guess is that, especially old folks who kind of remember the Village vaguely in the old days, that this will be not a nostalgia trip as I hope, but a way to kind of close the gap between the past and the present.

When were your first exposed to Bob Dylan’s music?

I was exposed to his name before I was exposed to his music because I remember my dad talking to [Folklore center proprietor] Izzy [Young] about him. Izzy said, “There’s this great new guy in town, you got to listen to him,” and then he proceeded to give my dad a Greenbriar Boys album. I don’t know why he didn’t give me a Dylan album, but I’d heard his name.

Then when Freewheelin‘ came out, I remember I was in a Sunday school class in Brooklyn. There was a very, very hip slightly older girl I was no doubt lusting after. She came in with this record, and it was almost like holy scripture already. This would’ve been, I guess sometime in ’62 or ’63.

Then you saw him at Philharmonic Hall in 1964.

Yeah. My dad had a couple of tickets, and I went with my cousin.

What’s the strongest image in your head from that performance?

I remember seeing him, and Joan [Baez] was there too. She was wearing this sort of weird Scots cap, which was very strange because I don’t think of her as a Scots woman, but it was more the music itself that left an impression because it was way over our heads. There was the stuff that everybody knew that he sang, like “The Times They Are A-Changin’” and so forth, but then he debuted “It’s Alright, Ma,” “Gates of Eden,” and that was the stuff that I remembered thinking, “What is this about?” None of us understood it particularly, and there were no lyrics in front of us.

To really understand the breadth of Dylan’s work, fans had to dive into the bootlegs. This just wasn’t the case with most other artists. If you wanted to understand the Beatles, the albums got the job done. There wasn’t this whole hidden cache out there of other things that deepen your knowledge.

Yes. Also, Dylan improvised in a way the Beatles didn’t. When they went on stage they played the same thing that was on the record. With Dylan, there would often be something new. He always wanted to do his new material. This is the hallmark of a Dylan concert. He’d play couple of things you would’ve heard, but he was very, very eager to get his new material out there, and that was always very special too.

That said, we knew there was a world of recordings, a world of music that we’d never heard, and that’s what we wanted to hear. We wanted to hear him sing the folk songs. We wanted to hear the songs that hadn’t really come out. There was a lot more there we knew, and the bootlegs just brought that out.

It’s amazing how often he was recorded when he was a very unknown artist. This just isn’t the case for the Stones, Beatles, Who, Beach Boys. Recordings of their early live concerts simply don’t exist.

What is important to realize is that there was a real community in the Village, which I don’t think that any of the others had. There was a world around Liverpool, sure, but there was a real community in the Village that was about more than just music. It was a way of life, really.

A lot of the recordings we have are Cynthia Gooding recording for her show on WBAI or someone just happened to have a tape recorder at the Folklore Center or something like that. But Gooding, among others, was very aware that there was a culture that had to be recorded, and they were going to record it any way possible. And she did a very good job of it.

And then there’s Terri Thal’s tapes too. I mean, she was the manager, but there they are. But it was a community, and this is another thing we try to get across in the Bootleg Series. It wasn’t just Dylan himself. It wasn’t just Dylan at Columbia Records. There was a whole world of the Village that was recording stuff.

Up until now, the Bootleg Series was produced by Jeff Rosen. How did this one wind up in your hands?

That’s a good question. Basically, I’d heard these rumors and nothing seemed to be done. [Former Sony Legacy head] Steve Berkowitz and I had a conversation one day and we said, “What’s going on here?” I approached Jeff [Rosen] and one thing led to another. The next thing you knew, I was doing this thing with Steve. Jeff offered it to me, and I very gratefully accepted the chance to do this.

It was more than just writing the liner notes because I’ve done that before. This was a chance to actually learn a great deal being in the studio with not only Steve Berkowitz, with [producer] Steve Addabbo as well. I learned a great deal about how you go about doing this kind of thing.

We’ve heard some of these tapes before, but they were often copies of copies with pretty horrid sound. I presume they tracked down the masters for this.

I don’t know much about the background. That was very much the office’s doing, Jeff [Rosen] and Parker [Fishel]. But we still had to do a lot of work on the tapes that we had. I’ll give one example, the stuff from [the July 6, 1963, voter registration rally in] Greenwood, [Mississippi], because that’s really patched together. Steve did a brilliant job, but what we had was very rough. We didn’t even have a full tape of “Only a Pawn in Their Game.” We had to stitch that all together, so there was a lot of work to be done in the studio.

The tapes, as good as they are, there’s always room for improvement. I was listening to it with my ear for a particular thing, and then Steve would figure out what he wanted, and we went on from there. He’d do all the technical stuff.

Tell me your initial thoughts about how to frame this, since there was so many ways you could have gone.

As a historian, the first thing is chronology. Where are you going to begin, and where are you going to end. We knew we wanted to begin in Minnesota, as close to Hibbing as we could get. That stuff had been out there, although not the Jokers stuff. That had not been heard widely. It was great to have that there, just to have a 15-year-old Bob Dylan having fun with doo-wop with his cousin and friend.

That was easy, the beginning. The question was where to end it, and I went back and forth about this in my own mind. We could have gone through ’64 if we wanted to because there’s a wonderful tape of that one night in July of ’64 where he records Another Side of Bob Dylan. You could do that. It would be fascinating because it’s an interesting tape and lots was going on there. So do you go that far? Where are you going to cut it?

It fairly quickly emerged that Carnegie Hall ought to be the end point. It really is a culmination of everything he’d been doing before. There is a significant break thereafter. Kennedy is killed in November. He meets Allen Ginsberg in December. He’s in a very, very different place, so by the time that Another Side comes out, people like [Sing Out! editor] Irwin Silber and so forth are going to be angry at him already even though he hasn’t even played an electric guitar.

There had been plans to release that concert, and it never really happened. There was a cover made up, but the record was never released. Some of that stuff has been out there, but what’s missing from it is not only the other tracks, obviously, but the response of the audience. What’s going on in this concert? It’s an event. It’s an extraordinary event.

Town Hall was first. Suze Rotolo described it very, very well. Town Hall was something special. They knew that something special was happening at the Town Hall concert. But Carnegie Hall is a different matter. There is where you see him in his full…this is Bob Dylan in his full blossoming as Bob Dylan. He’s then going to be another Bob Dylan, and many other Bob Dylans, but that is the culmination of it.

The set starts with Dylan, his cousin, and his camp buddy singing “Let the Good Times Roll” in a music shop in 1956. How did that surface?

I don’t know. There’s some things I don’t ask about. As long as we have it, that’s fine, good enough for me. But what it shows is, first of all, his early enthusiasm for doo-wop, and rhythm and blues. He didn’t start up as a folk singer, and there’s no better way to show that than hear him as a 15-year-old singing Shirley & Lee, or Little Richard, or what have you.

We read about it, but there’s no recording as far as I know of him with his bands in Hibbing. So this is him in his very early stage. If you listen hard enough, you can hear his voice. He’s the one who’s banging on the piano, and he’s the one who knows all the lyrics or most of them. It’s unclear what the other two guys do, but you can hear his enthusiasm for this stuff, and it’s a youthful enthusiasm. They don’t quite find a groove or anything like that, but they really love this music.

You can’t understand Bob Dylan without understanding Little Richard from the very beginning, so there was a chance for us to do that. We chose the Shirley & Lee because I thought it was the first cut that they made that night in 1956. It’s the very, very first, but it was also a rendition that I thought was fun, so we put it on.

Tell me about this rendition of “Jesus Christ” from 1960.

He is doing Woody Guthrie his own way already. He has said that he was a Guthrie jukebox, and that’s true. He spent a lot of time singing Woody Guthrie songs, although not only Woody Guthrie’s songs, which is another point we want to make, but he’s doing it his own way. He’s not doing it the way that you would’ve heard it on a Stinson [record] or on the Library of Congress tapes or whatever “Jesus Christ” first appeared. He did it his own way, and that’s important to understand about Dylan from the start, even before he starts writing his own material.

He is not interested in replicating. He is not interested in imitating, as many people in the Village would end up doing and that’s fine. From the very beginning, he wanted to do his own way, and you hear that even in 1960 on a tape in his own apartment. I would invite people to go compare Dylan’s version of any of these songs with those of the people you heard it first, including Woody Guthrie.

I loved hearing “Remember Me” from Bob Gleason’s house right after he got to New York.

Yeah. He gets out to the Gleasons pretty early on, which has a number of different meanings, layers, because he’s basically adopted by this very charmed circle of people around Woody Guthrie. The Gleasons were great. They have him out to the house before he’d even really arrived. And he’s hanging out with the likes of Pete Seeger, and Cisco Houston, and all the people that are going to be [mentioned] on “Song for Woody.” He’s already meeting them very early on.

The thing about “Remember Me” apart from everything else is Dylan’s voice. This is a Dylan voice that people are not expecting when they think of the early Bob Dylan. It’s much more like the voice actually that he’s had back in Minnesota. He’s crooning more than he is Guthrie-ing his songs

One of the things we wanted to do with this was to change pace, to throw people off a little bit, to challenge their expectations of what an early Bob Dylan would’ve sounded like, and how he was going about learning how to perform, and he’s learning how to perform by singing songs like this.

Right. People often think he was using an Okie accent in this time.

And continued to do so. You can’t understand Bob Dylan without understanding his many, many voices.

You put in “Talkin’ Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues” pretty early. It really shows how funny he was, and how he could take a story out of a newspaper and turn it into that.

Well, he could take a story that was kind of a downer and turn it into a frolic. One of the things about the [Timothée Chalamet] film that they didn’t catch was how funny Bob Dylan was, and is. He’s hilarious. He’s making jokes all of the time. One of the things about the Village that people don’t really get is they think of the Village as a music place, and it the very places that they played, in fact, like the Gaslight. Woody Allen was getting a start there. Richard Pryor was getting a start there. Bill Cosby was there.

Everybody listened to everybody else. We leave it off the record because it just gets too long, but he has like a four-minute monologue before the song actually begins. He’s setting the whole thing up in a very humorous way, and people are laughing, and you can hear that on the recording that we have too. I mean, it is just hilarious.

There’s a lot of recordings of him by Bonnie Beecher when he went back to Minnesota in late 1961. It’s interesting to hear them because the New York people always say he took this quantum leap forward when he came back after that trip.

That’s true. It’s funny because the people in Minnesota thought he was nothing special, then he comes back from New York and he looks like he’s just been at the crossroads. Where was the crossroads, in Minnesota or was it in New York?

But the point of all this is that he was improving by leaps and bounds. Improving, that’s not the right word. He was discovering himself, discovering new stuff. He was insatiable, and he was working very, very hard. That’s the other thing I think we want to get across, is that genius is not just born, genius is made, and it’s made by the genius himself. You can hear Dylan on a lot of the cuts here working very, very hard at mastering his craft.

Bob’s life story has been told a lot, both by him and by others. But he’s such an unreliable narrator. And the people who speak to biographers about these days are relying on very old memories they’ve recounted many times. The whole story starts to get really warped. What’s great about this bootleg series is it tells the story of this time solely through the music.

Well, in some ways a lot of Dylan’s fakery of his own bio has always been very amusing. He’s been doing this from the very beginning, he’s never telling anybody the truth about who he is because he doesn’t want people to know who he really is. He wants people to know him through his art. He wants people to know him through his work, and what we’re presenting is that.

I’m less interested in what Bob Dylan had for breakfast on any given day. I actually don’t care about that. Some people are obsessed with it, I don’t care. But I really care about what he sang that night, and what he was saying into a tape recorder at Mel and Lillian Bailey’s house to try to figure out a tune or something new. That’s the process that I’m interested in.

These party tapes are really interesting since he’s performing very differently than he does at a coffee house or folk club.

Yeah, and it’s a different community too. When he’s playing in Minnesota, when he’s back in Minneapolis, these are old friends from college days. There are people who are growing up with him and with the music. I think of Tony Glover above all, and he’s showing off to them what he’s done in the city. At first, it had to do with the fact that he met Woody Guthrie, and he was very excited about meeting Woody Guthrie, and he’s writing all about, “Well, I met Woody, it’s so great.”

But then it’s about how he’s perfecting his craft, and they’re meanwhile perfecting their own too, especially somebody like Tony. So it’s a kind of meeting of people who are friends, but they’re also showing off to each other, they’re also showing what they can do, what they’ve picked up.

It’s not a one-way street. It’s not just Bob showing his friends where he’s been. These are people who are in the know, many of whom actually thought of him as kind of a loser, as kind of an imitator. Now he’s coming back and showing them, and they’re going to show him what they know, and they kind of go back and forth.

It’s not just in the music, it’s actually in words as well. There’s stuff on the tapes that we couldn’t put in that have him in conversation with people. There’s a great conversation with Paul Nelson about the character of folk music. So these are people who are not living together anymore, but came up together, whom he trusts, whom he has great affection for, but they’re also growing up together and learning from each other, and that shows up on the tapes too.

You went through the raw session tapes from his first album session with John Hammond. That must have been interesting since he’s never recorded his songs in a studio before. It was a very foreign environment for him.

Absolutely, and folk music is sort of a foreign environment for John Hammond, who’s a great jazz producer. We have a rehearsal of “Man of Constant Sorrow,” and you can hear John Hammond’s kind of perplexed about what this song is, and any rate, they’re learning it together.

What really impressed me about those tapes was how much he had learned between January and November of ’61. When he gets into the studio, the first album is kind of thought of as a juvenilia, as his first attempt to do something. Well, no. First of all, for the Woody Guthrie jukebox talk, Bob Dylan has never released a recording of him singing a Woody Guthrie song. There are two of his own songs on there. But my favorite outtake from that session is him singing the Woody Guthrie song “Ramblin’ Round,” which is just a stunning performance.

He is growing almost daily, but he’s far different, far more possessed. He can enter a song in a way that he always wanted to, but had to teach himself how to do over eight months or however long it was.

The April 1962 Gerde’s tape is pretty extraordinary. You get to hear “Blowin’ in the Wind” before it’s even finished. It’s amazing that tape exists.

It is, and nobody knows who made it. We tried to find out, but it’s one of these anonymous things. I’m sure there are people who claim to know, but we couldn’t track it down.

In the space of four songs you can hear Bob Dylan moving from where he had been when he recorded his first album back in November ’61 to “Blowin’ in the Wind.” It’s in a club, you can hear people cheering him. He has a following now, the very first. We have an earlier Gerde’s performance and there are only six people showing up. It was a Sunday, true, but still there was nobody there. Now he has a following. You can hear the following there, and he’s responding to the following.

But then out of nowhere comes this song that nobody was prepared for, that he had just written, which he said he didn’t write, but he just recorded it. He’s always had this idea that he doesn’t write the songs, the songs write themselves, and they could just flow through him, he says that then.

You also got the ambiance of what a club was like, which we wanted to capture as well. He does have a following, they are yipping and yapping and having a good time, and he’s joking back and forth with them too. We wanted to get some of the intimacy of Gerde’s. We wanted to get Gerde’s across along with getting Bob Dylan across.

The Riverside church tape also has great moments. They recreate it in the movie since it’s where he first met Suze.

Our big discovery was there’s a guy who comes on and introduces Bob Dylan as Bobby Dylan from Gallup, New Mexico. “He’s been singing around town, and he sings a lot of Woody Guthrie songs, and so here’s Bobby Dylan.” We didn’t know who that was, who introduced him, so we all went on a big search to find out who — we discovered it was Bob Yellin from the Greenbriar Boys. He’s still around, and he was able to confirm that was his voice.

That is where he first lays eyes on Suze, although the film distorts it a bit. He sings a song with Jack Elliott. He sings a song with Danny Kalb. This was a community event. It was an all-day folk hootenanny. This was a community. They were all there together. They were all having fun. If you hear the whole tape, you get that sense as well.

Bob made the first albums in two days. Then Freewheelin’ took the better part of a year. In listening to the session tapes, did you gain any insights into it?

I think that it’s a manifestation of his rapid growth. They had a lot of tracks early on, but they weren’t satisfied with it. He wasn’t satisfied with it. He had other things to say. He had other things to write, so there were these big gaps, and then there would be these gaps for a bunch of reasons that the notes help to explain, but he wasn’t really satisfied.

They did the famous experiment where John Hammond has the idea that he wants to get a single, so he’s going to put Bob with a big band, and they’re going to record this song that he wrote called “Mixed Up Confusion.” They’re actually going to record a lot of Elvis because Bob wants to be Elvis too. So they record “Mixed Up Confusion,” backed up with a kind of jacked-up version of “Corinna, Corinna,” which we’d heard him sing earlier in the Village, and boy, did it bomb. They release it as a single and it doesn’t take off.

So there’s a lot of fits and starts in making that record, and then they thought they might’ve had the whole thing done when it goes off to England in December of 1962, and that’s a whole other rebirth. He learns a whole new set of things. He’d not really been in touch with Anglo-Celtish, Scottish songs anywhere near as adept as he was going to get when he was playing the folk clubs in London. He’s hanging out with Martin Carthy in particular, and learning all sorts of things from him. So by the time he comes back to America…he’d written “Masters of War “while he was in London, and then he goes off to Greece afterwards, and he writes “Girl From the North Country,” and “Boots of Spanish Leather.”

They end up putting “Girl From the North Country” on [the album]. But the album only became itself after he came back from London. And because of another famous dispute, they had to take four songs off. They had to take the John Birch Society song off because CBS was worried about getting sued. Then Grossman had also replaced John Hammond with Tom Wilson, and it’s unclear how much different the songs would’ve been if Hammond had produced them, but nevertheless, they do this all at the very last minute.

The record had been produced, it was ready to be shipped, it was all ready to go, and then they have to make a new one. Freewheelin’ is in many ways his real breakthrough as a songwriting genius. But it was a patchwork of different phases of that year and a half.

The box set devotes a lot of time to the summer of 1963. That was such a crucial time because of the Newport Folk Festival, the March on Washington, and then he’s in Greenwood too.

The summer of ’63 was important historically. In many ways, it’s the crescendo of the Civil Rights Movement and of Dr. King. It’s Birmingham. All sorts of things are happening in the Civil Rights Movement, really violent things that are changing the character of what the movement was about. It’s going to be pushing the Kennedy administration to a kind of open support that it had never given before.

Dylan’s in the middle of all of that. He’s not going to join any picket lines, he’s not going to lick envelopes. Suze very much was. But it was in the air. I mean, he’d written about Emmett Till in early ’62, so it was something that he was responding to. You couldn’t help but respond to it at a deep emotional level, which is where Dylan’s music comes from, from inside him.

The Greenwood event happened because Theodore Bikel convinces Grossman to allow Bob to come down to Mississippi, where they’re going to have a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. That area had been dark and bloody ground. It was really dangerous to be there, but Bob went along with Bikel and Pete Seeger.

As John Lewis later said, it was the first time that Blacks and whites together were singing freedom songs in the Mississippi Delta. That might seem like, “So what?” But it was not, “So what?” It was a big deal.

It’s not remembered anymore particularly, it’s remembered maybe only because of Don’t Look Back, but it really was an important statement at that moment, and for him to sing for the first time publicly “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” which shook people up. It’s not a simple story at all. It’s showing that there’s a system involved here rather than just good and evil. It’s complicated.

And then he sings “Blowin’ in the Wind.” The answer is blowing in the wind. Well, okay, what is the answer? We’re never told what the answer is. So it’s Dylan at his most thoughtful, but also very clear where his heart and his mind are, the Civil Rights Movement. He’s literally putting his body on the line. There are cops all over the place. It’s a scary scene.

Very soon after, there’s the March on Washington at the end of August. And Dylan is much closer to the Civil Rights Movement, and the young people in the Civil Rights movement than I think people have realized.

I think they conflate it with the Vietnam protests and just presume he wasn’t involved in any of it. But he was very involved.

Very involved. I mean he’s hanging out with them, they’re friends. Now, his job is not to write speeches, it’s not to go on the line and say, “I’m for the…” He’s going to write his songs, he’s an artist. So he’s involved, but he’s involved in a very particular way.

Then you have the Newport Festival afterwards where they kind of reenact Greenwood at the very first night when he calls up Seeger, and the Freedom Singers. The same people who have been at Greenwood are now on the stage in Newport, except it’s a whole different scene. There’s no cops. It’s like everybody is adoring him, and they sing “Blowin’ in the Wind.” It blows your mind.

Then he goes and records The Times They Are-A Changin’. I love the version of “One Too Many Mornings” you picked out for this.

It was very important to have “One Too Many Mornings” on there because there is this political move that he’s making. He goes out to Carmel and he’s hanging around with Joan Baez, and with [Richard] Fariña, and Mimi Baez. Joan said the songs were coming out like ticker tape. He writes all of these songs, they’re coming off of him like crazy, but they’re not all political songs.

“Lay Down Your Weary Tune” is kind of a taste of things to come in many ways. That’s not a political song, it’s about to nature and the imminence of the holy, and all the rest. Then he does do “One Too Many Mornings,” which I think is one of the greatest songs he ever wrote. That, again, it’s of a piece with things he’d been writing a year earlier, there’s “Don’t Think Twice,” and there’s “One Too Many Mornings,” and I see there’s a connection between those two.

They both have to do with love and regret, and a certain degree of bravado maybe in the first song, and a certain degree of remorse and regret on the second. But the thing about Dylan is that he thinks at many different layers and holds them all together at the same time so he’s not going to be any one thing, and you can’t put him in a box.

People put him in periods, and yeah, there are periods, I suppose, to his music. But there’s always something else, many, many other things going on at the same time, and you cheat yourself if you try to restrict it to any one of those things.

What do you hope they pick for the next chapter of the Bootleg Series?

Well, that’s endless. There’s all sorts of things I wish that they’d released. I’d like to see the Another Side session brought out. You could do it probably on one or two CDs. It wouldn’t be much to do since it’s just a few hours, and there’s so many wonderful songs on that record. There’s all the stuff that he did with David Bromberg. We’ve never heard that material.

I keep hearing rumors about an Oh Mercy box set.

Oh Mercy would be obvious because of [producer Daniel] Lanois and what he wrote about in Chronicles. You could wrap it around that whole moment in his career. The tapes are all there.

What I’d really love more than anything is a 1978 box of Street Legal material and the tour that year.

The Street Legal tour is much underestimated. People jump right to the gospel stuff, but they forget that there was this tour out there before. Did it do well? I can’t remember.

It played to arenas that were pretty full. But this was happening right when Bruce Springsteen and Neil Young were peaking with Darkness on the Edge of Town and Rust Never Sleeps. Those are basically two of the best tours of all time, and critics often compared Dylan’s tour to them unfavorably.

Well, he survived. There’s lots of good stuff that people don’t remember as good stuff. I don’t know how long they’re going to be bringing them out though. They could go on forever, I suppose, but we will see.

I’m sure after being a fan your whole life, it was a dream to be the one putting one of these together.

Oh, beyond. And the book itself is just so beautifully done. I sometimes said that the book I wrote about Bob was really about my father, and it was really about growing up in the Village. It was a way of trying to desublimate that stuff. It was somewhat refracted.

This wasn’t about that because I’d settled my scores in that book, but to go back there, and to remember it all, and to hear it…I mean I’m 10 years younger than Bob Dylan, so I was a kid. I was a close to it, I could almost touch it, and I did go to Philharmonic Hall, but I was a kid, and so to hear it now at a ripe old age is really… well, I can’t even go into it. It’s very personal. I still have dreams about it.