Cyndi Lauper leading the crowd at the first MTV New Year’s Eve party at Times Square.

Photo: Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images

The news that MTV is shutting down its music channels does not come as a surprise to me. Starting in 1986, I ran MTV, VH1, Nickelodeon, Comedy Central, and other cable TV networks for 17 years as the CEO of MTV Networks, the sun in Viacom’s solar system. It hasn’t been that for a while. MTV has been losing credibility for years, and it’s devolved into a dumping ground for B-grade reality shows. No new music energy has been pumped into it for ages.

Only the U.K. music channels are affected for now, but the United States can’t be far behind. The business case for running music videos on a linear TV cable network in this increasingly digital, on-demand world is terrible and only getting worse. Why sit around and wait for Beyoncé when you can summon her video with a simple click?

David Ellison, who recently acquired Paramount Global from Viacom, has an opportunity to step back and try to reimagine MTV as a new destination outside the confines of a linear TV network. The music space is now dominated with increasingly predictive and boring algorithms. Maybe there is a way to shake up at least a corner of the huge music market like we did back in 1981, when I was just the marketing guy arriving at the start-up that would become MTV.

After we busted through the cable-operator gates with “I Want My MTV,” we became the new gatekeepers. Everyone wanted to be on MTV. Labels and artists lobbied to get their videos in heavy rotation. We could catapult nobodies to stardom in weeks. There was a lot of power to wield, and power doesn’t always bring out the best in people.

We were in the Zeitgeist business, so we took a lot of chances with new things, not always successfully. If something didn’t work, it died a quick death, and we moved on. We decided we weren’t going to grow old with our audience the way Rolling Stone magazine had — they were still writing about Bob Dylan and Eric Clapton. We would refresh and reinvent MTV every four to five years as one group aged out and a new one replaced it.

Advertisers pay a higher premium to reach young people. The thinking is: Hook them on Crest or Pepsi or Ford early on and you’ve got a customer for life. When MTV said, “We have a direct line to them,” Madison Avenue lined up at our door.

One by one, record labels agreed to give us clips for free, and they set up whole departments dedicated to servicing MTV. But they never stopped grumbling. They complained about the money they had to spend to increase the quantity and quality of their music videos. So we agreed to pay them millions of dollars through new, multiyear “output deals.” Buried in those deals was a clause granting us exclusivity for six months over any other 24-hour channel on 20 percent of their music videos. The 20 percent of the videos we picked were all the big hits. No potential competitor could take a run at us without access to the hits.

I was against using hard-nosed tactics with the record companies and artists. Gatekeepers with a heart seemed the best way to prolong our prominence. As “the biggest radio station in the nation,” I argued, we should be fair, humble, and walk softly; the labels were predisposed to resent us. My opinion didn’t always carry the day. I watched some of our talent-relations people blossom into megalomaniacs. I guess it’s human nature that if you are hanging out on boats with Billy Idol and partying with Van Halen and strolling into every dressing room while giving thumbs-up or down to anxious managers, it will eventually turn you into an asshole. I saw it happen again and again.

A recruit to the Music & Talent department with good ears and a deep knowledge of pop and rock might last three years. To fire them, we might have to find a concierge to kick down a door in an L.A. hotel and revive them after a three-day cocaine binge. We needed a strong human-resources department.

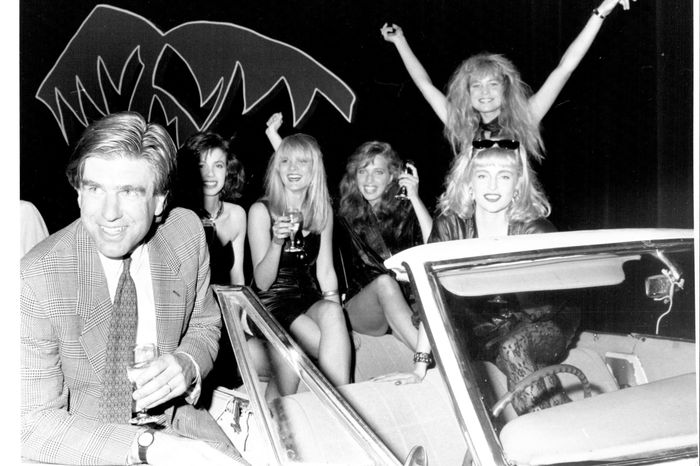

Tom Freston at a promotional event in 1987.

Photo: Alan Gilbert/Fairfax Media via Getty Images

We were witnesses and eager participants in the last display of the legendary excesses of the music business. The party really kicked into gear when Bob Pittman made former radio DJ and label executive Les Garland the head of programming. Les was the one who had gotten Mick Jagger to scream, “I want my MTV.” He referred to himself in the third person as “the Gar Man,” which tells you a lot. Les Garland wasn’t his real name. Like many former radio people on our staff, he created a radio name. “Les Garland” was really Lester Schweikert.

He looked about my age, but to this day I don’t think his date of birth has ever been revealed. He was an effervescent, good-looking guy with stylish curly brown hair, confident that he was the king of cool. In many ways he was. MTV’s fingers were in every pie of the music-industry machinery and for a while, most things came through or went out from Les. He arrived with deep music-business relationships, full of war stories from the rock-and-roll trenches of the ’70s, which he recounted to entertain his younger minions. It was like David Lee Roth had arrived in an Armani suit and taken over the floor.

Amid towering speakers, gold records, stacks of videotapes, Sony Trinitrons, overflowing ashtrays, and a bar stocked with tequila and a lineup of squat green Dom Pérignon bottles sent over by the labels, the Les Garland Show streamed. Every time a big ad sale landed, he rang a huge bell. Grizzled label-promotion men in satin jackets and facial hair would slink in and out, usually laughing. Rod Stewart would drop by to play his newest tracks. When female artists came calling, his staff would vacate, and according to office lore, the Gar Man would fornicate with a lucky few. At least, that’s the legend. With Les, it was hard to tell what was true, what was myth, and what was scandal.

When he wasn’t there, others would sneak in to have sex in his office. At one Christmas party, a staffer full of holiday bravado cozied up to Garland and said, “Les, I just want you to know that I fucked one of your assistants last night on your desk.” Les clinked his glass, said, “Congratulations, Bud,” and walked away.

Big blowout parties became part of company mythology. “Tequila girls” in short shorts and cowboy hats, decked out in bandolier sashes packed with shot glasses, always circulated. Tequila bottles were nestled in holsters strapped across their hips. Bands like the Fabulous Thunderbirds would play. These parties could go on to three or four in the morning, sometimes devolving into after-parties. You could never get away with this kind of office party nowadays. Nonetheless, the next day, a line would form outside the human-resources offices.

The Gar Man undeniably upped our game, our profile, our whole tempo. I had spent nearly a decade in the 1970s running a clothing export company out of India and Afghanistan and to me, MTV was a lot like Kabul. An exotic new place with a crazy cast of wild characters and few rules.

A superfan myself, I had the privilege of attending any concert I wanted. Every day we dealt with the biggest stars in the world, along with all the black sheep and characters who handled them. Even though music drove the culture, the business of music was still considered the lowest rung of the entertainment ladder. To people in film and television, it was a lowbrow world of payola, shysters, and semi-gangsters in sharkskin suits. But these were the folks I liked the most. They had hustle, were clever, and loved music. They were also the most fun. Some label heads, like Gil Friesen, who ran A&M, Jeff Ayeroff, who ran Virgin, and Jimmy Iovine, who ran Interscope, became good friends. Many in the MTV crowd had not been to or finished college. I went undercover with my academic credentials. It sounded a lot better to be “the man from Afghanistan” than the M.B.A. from NYU.

People worked in flip-flops and bathing suits; some slept in their offices. In 1988, at 2 a.m., an overnighter flipped a lit cigarette into his garbage can and burned down a whole floor at 1775 Broadway. Nineteen firefighters were hospitalized. The local radio stations would play Springsteen’s “I’m on Fire” and dedicate it to us.

“Exotic dancers” would be sent over by the music labels. Bands passed through all the time. Lemmy from Motörhead might wander by with a bottle of tequila. We had one receptionist who sold cocaine. Many of the staff found that convenient. Cocaine was rampant in the ’80s, especially in the music industry. Even your dry cleaner was doing it then. People thought coke was the new No-Doz, a harmless pick-me-up powder.

One of the programming guys, a jovial, former radio hotshot whom Howard Stern had crowned “Pig Virus,” kept his stash in a little plastic receptacle in his desk drawer, the place where you’d put paper clips. In a meeting, he’d nonchalantly open the drawer and take a hit off a collar stay, then politely look around. “Anyone need their beak packed?”

MTV wasn’t a job; MTV was a life. We were a second family. People would duck out all the time to the bar around the corner. At night, there was always a smorgasbord of things to choose from … concerts, dinners, listening parties, movie screenings. We were in the middle of everything, so we were invited to everything. Not everybody made it out the other side; there were casualties with all the late nights, alcohol, and drugs. No one except me had a family. Margaret and I had a young son, Andrew, at home, which kept me pretty much on the straight and narrow. Once he went to sleep, I could head back out on the town.

To try to prop up the business side and bring order to the chaos, Pittman installed a series of general managers. They didn’t take. One, David Hilton, undermined his predecessor and then went down in flames. Hilton had zero music chops, which earned him zero respect. I’ve never seen anyone do a worse job at anything. He sent around a note to announce that if anyone was even one minute late to a meeting, they’d be locked out. He locked his door and put a chair under the doorknob. Sometimes we’d all be purposely late so he’d have to have his meeting by himself.

Robert Downey Jr. and Slash at the 1988 MTV Video Music Awards.

Photo: Barry King/WireImage

In 1984, MTV held the first Video Music Awards at Radio City Music Hall. We were positioning ourselves as the irreverent alternative to the self-serious Grammy Awards. Bette Midler and Dan Aykroyd hosted. The Cars’ “You Might Think” won Best Video, and Herbie Hancock’s “Rockit” won pretty much everything else. Madonna rolled around on the stage in a wedding dress while singing “Like a Virgin,” and a star was born.

When MTV began, we played almost any video we could get our hands on. As we proved our ability to sell records, the bigger stars with bigger budgets pushed aside the punkier stuff. The record companies began to crank up music-video production. Instead of four or five new clips a week, we began to get 50 or 60. Big star holdouts like Bruce Springsteen joined in. Older acts like ZZ Top reengineered their image. Lionel Richie spent $1 million on his “Dancing on the Ceiling” video.

As MTV became more influential, we also got more scrutiny, and not just from the Christian right. The criticism that stung was that we were not playing Black artists. In a very awkward interview with VJ Mark Goodman, David Bowie challenged him about the channel’s color line. Rick James went on a public crusade about us rejecting his “Super Freak.” He was right.

Rock radio went backward after the 1960s, when the Beatles and Stones shared airtime and formats with the Supremes and Aretha. The early MTV music programmers came from the world of ’70s FM rock radio, which relied on a format called “album-oriented rock,” or AOR. It was a very researched system but predicated on an underlying racism. “Our audience wants to hear a guitar,” was the refrain from the programming guys. AOR resegregated rock and roll.

In the 1980s, the record companies all had “Black Music” departments. The trade magazines, Billboard, Cash Box, and Radio & Records, all had separate Black Music charts. It wasn’t just MTV. But we were the only music channel on television. Early MTV did play some Black artists who fit the AOR format — Joan Armatrading, Grace Jones, Eddy Grant’s “Electric Avenue.” We gave heavy play to Prince’s “Little Red Corvette” and “1999.” But that doesn’t excuse the sad fact that the music department would put Hall & Oates doing R&B in heavy rotation, while ignoring Luther Vandross and the Brothers Johnson.

The wall was finally knocked down by Michael Jackson’s Thriller. CBS Records chief Walter Yetnikoff always claimed that he forced MTV to play Michael Jackson by saying that if we did not, he would pull all Columbia and Epic videos from the channel. It’s a good story, but I have never found anyone who worked at MTV who had any idea what Walter was talking about. “Billie Jean” was a smash from day one. We wanted that video on our channel. “Beat It” was even better. By the time MJ released the video for “Thriller” toward the end of 1983, he and MTV were in a mutually beneficial relationship. We played his 13-minute mini-movie on the hour, every hour. I ran ads in People magazine with start times. Our ratings went through the roof, and so did Jackson’s album sales.

In the late ’80s, we opened the aperture further. We were the biggest music outlet in the world; there was no need to follow anyone. MTV would be the first to mainline hip-hop into Middle America’s living rooms with Yo! MTV Raps, hosted by downtown Renaissance man Fab 5 Freddy. Aerosmith and Run-DMC sanctified the rock-rap connection with the clever video “Walk This Way,” and we were off into a whole new world.

But before that came our next powerhouse: the July 1985 16-hour Live Aid extravaganza held simultaneously in London and Philadelphia. At the time, it was the biggest satellite linkup and television broadcast ever. It raised almost $200 million for African famine relief and would set a template for the many all-star fundraising concerts to follow.

Paul McCartney, Elton John, and David Bowie were on the bill in London. Fans saw a career-making performance by U2 and a showstopper by Queen. Phil Collins performed at Wembley, then jumped on the Concorde to play another set at JFK Stadium in Philadelphia, where Mick Jagger tore off Tina Turner’s skirt.

I rented a car and drove from New York with Bob Friedman, my eager marketing foot soldier, known internally as “the V” for reasons no one remembers. When we got there, we realized our credentials were in the hands of a producer who had disappeared. This was the pre-cell-phone era. There was no one to call. We finally found our way to the artists’ enclosure and jumped the fence. I landed in the dirt right in front of Bob Dylan’s trailer, dusted myself off, and then calmly strolled down lanes of trailers, striking the pose of someone who belonged.

It was like wandering through the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame trailer park. Signs read: Tom Petty, Santana, Madonna, the Beach Boys, the Four Tops, Neil Young. We finally made it to the stage, and I spent the entire show at our news desk, 20 feet from the action. Live Aid was the final step in the legitimization of MTV. We were now like “Kleenex” and “Coke.” That year, we made the covers of Time and Newsweek. As for David Hilton, Pittman finally showed him the door and crowned me general manager. It was my 40th birthday. I had finished my apprenticeship and was ready to run the beast. I got a very warm welcome. Always follow an unpopular person into a job if you can.

Copyright © 2025 by Tom Freston. From the forthcoming book UNPLUGGED: Adventures from MTV to Timbuktu by Tom Freston, to be published by Gallery Books, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC. Printed by permission.

Want to be emailed when products you’ve saved are over 20% off?

Success! You’ll get an email when something you’ve saved goes on sale.

Yes

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(jpeg)/GettyImages-1365294801-66eeef3fc5e3424c854395c8a13e1b1c.jpg)